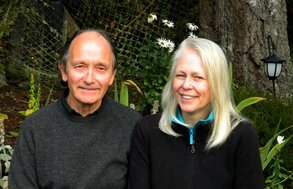

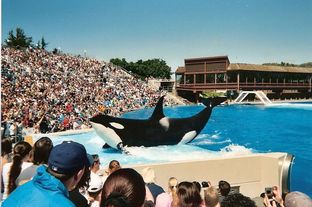

Paul & Helena Paul & Helena Dr. Paul Spong is an orca researcher and the founder of OrcaLab, an orca research station off Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. Since the 1970s, Dr. Spong, his wife Helena Symonds and their team of volunteers have helped to spread awareness of the Northern resident orcas, giving an invaluable insight into this community's lives. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------  Northern resident orca 'A33' (Photo: Rob Lott) Northern resident orca 'A33' (Photo: Rob Lott) Suzie: Tell us a little about yourself, Paul. What led you to study orcas? Paul: I started in quite an obscure way. I was involved in doing brain research for my PhD, during the early days of computer studies of the electrical activity of the brain. I was involved in some experiments that were looking at pathways in the brain which are used to process perceptual stimuli, and when I finished that work I was looking for a job. I applied for a job at the University of British Columbia [UBC] in the psychiatry department. It sounded really interesting, involving half-time neurophysiological research on the campus, and half-time behavioural research with a newly captured orca. I knew nothing about orcas, but on the UCLA [University of California, Los Angeles] campus there was a very well respected cetacean scientist. He told me that a lot was known about audition (how cetaceans process sound), but very little was known about vision. So he suggested that I put together a proposal to study vision in the orca, and that led me to UBC and to an interview for the job. When I walked into the lab at UBC to do this interview, on the bench there was a huge glass jar that had a brain floating in it; it was massive and obviously very highly developed – you can tell just looking at the surface convolutions. It was the brain of 'Moby Doll', who was the first orca who had ever been captured. Moby Doll started off the whole idea that orcas weren’t these fearsome creatures and a total threat to humans, so some years later the Vancouver Aquarium had brought a whale exhibited at the local boat show and eventually housed her in a small tank intended for dolphins. They chose the name 'Skana', (a First Nations name), and they went looking for somebody to do studies... That ended up being me. So really, my interest began with brains and my first introduction to an orca was an orca brain. And of course that got me thinking, “What on Earth is this creature, and what on earth does it do with this massive brain?” Suzie: What work did you initially carry out with orcas? Paul: I ended up working at the aquarium for a couple of years doing studies on vision with Skana. I started looking at the question of visual generalisation, which involved a very long series of trials that consisted of a choice. I built an apparatus with two sides; one side held a card with two lines on it, and the other side held a card with one line on it. I wanted to find the point at which she failed to discriminate the two. It took a long time to for her learn the initial discrimination, and at one point she refused to continue any longer. Rather than performing the exact task I gave her, she made precisely the opposite discrimination to the one I was asking for; so she pressed the wrong side. Her performance went from 100% to 0% correct. This got me thinking about the issue of ‘motivation’. I realised that only providing the whale with half a dead herring dispensed from an automatic feeder at the side of the pool wasn’t a huge reward. I started to reward her with other things, like retrieving a ball, and under that circumstance her performance went up to 50%.  Skana & Hyak (Photo: KE Wiley via orcahome.de) Skana & Hyak (Photo: KE Wiley via orcahome.de) Suzie: How did this revelation impact your work? Paul: By that point there was another younger whale ('Hyak') that had been captured in Pender Harbour and held in the aquarium. He was all alone and had become a very sedentary creature; he’d sit all day in the same corner of the pool mostly floating at the surface. I thought I’d see whether sound might be used as a reward, so I set up an acoustic experiment and it transpired that music was the form of stimulation that was most effective. He learned to swim around the pool for an acoustic reward in a very few trials; much fewer than Skana did in her trials. I then started to reward him for anything other than just sitting in the corner of his pool, and under those circumstances he became a completely different being. He would swim around the pool really quickly, sloshing great waves of water over the pool or leap out of the water. So it was very obvious to me that sound was an effective reward, but at the same time I started to realise that my attitude was changing. Suzie: Can you tell us how you started to feel about keeping orcas in captivity? Paul: I got attached to the whales. I got to know Skana and Hyak better, and ultimately came to the conclusion that what we were doing was quite unfair to the whales. I had observed the consequences of two captures and I was changing my attitude about captivity. I didn’t really intend it to happen, but eventually I became an advocate for sending the whales back to the ocean. After nearly two years of this work I did a lecture at UBC, from which a reporter from the Vancouver Sun published a story in the paper stating that I thought the whale should be returned to the ocean to re-join her family. That got me at odds with the aquarium, and not long after that my contract with the aquarium was coming up for renewal and they decided not to renew. Essentially, they fired me because I had disagreed with their attitude about captivity. Suzie: How did you transition into wild orca research and the creation of OrcaLab? Paul: I saw some interesting things up in Pender Harbour during a wild orca capture. For example, the whales remained very calm and didn’t attempt to escape, or make massive resistance to being lifted out of the water. I went up to Alert Bay, (which was at that time called 'the home of the killer whale') with my wife and our son to find out more. Talking to local First Nations people and fishers, I learned some very interesting things, especially from First Nation’s history, and subsequently put together a little expedition with a grant from UBC to observe orcas in the wild the next summer. One of the places we came to was on Hanson Island, which is on Blackney Pass. We built a little structure in a tree-house adjacent to the shore and we put equipment in it, then put a hydrophone in the water and started making recordings. What became apparent during those early days was that we were seeing the same whales over and over again, and we started giving them names. Shortly after, Dr. Mike Bigg and Ian McCaskey, (scientists at the Department of Fisheries and Oceans facility in Nanaimo, BC), became tasked from the federal government with trying to figure out how many orcas there were on the BC coast. The first whale, 'Stubb', who we had called 'Tulip', was given the ID 'A1' because she was the first whale in that ID study. The second whale we identified, 'Nicola', was given ID 'A2', and so on. By taking photographs they ended up identifying every whale on the BC coast; it took them quite a number of years. Suzie: And OrcaLab evolved from this first trip? Paul: Each year in summertime we went back to Hanson Island and gradually built up a facility there. We built structures out of driftwood and put equipment in there that enabled us to do recordings and look at orca calls with an oscilloscope. I played music to the wild orcas as I had done with the ones in captivity, but it turns out that they weren’t very interested at all! So at that point we stepped back and started just observing the orcas remotely. A friend named Bill ter Brugge, (an engineer at the local hospital), got hold of some old equipment at the coastguard station and started building a remote transmitter system for us. This was a real breakthrough as this enabled us to listen into spaces that were out of our sight in other areas. We started building other stations that enabled us to cover about 50 square kilometres of the underwater environment in the surrounding area. Just by listening to the transmissions, we could tell when the orcas were arriving in the area and it meant that we didn’t have to be out there following whales around in boats. We could then figure out what they were doing and eventually who they were. In the mid to late 1970s, a student at UBC named John Ford did his PhD on the sounds that the orcas made. He ultimately figured out that orca pods use dialects, which means they use a set of sounds that are unique to the pods. This became really important to us because when my wife Helena started listening to these sounds, she realised that the individual family groups that make up the pods also have dialects. By listening to their sounds with our equipment, and with the photo ID books that Mike Bigg and his colleagues had produced, we were eventually able to identify the individual family groups that we were looking at. It contributed significantly to our understanding about how the orcas of the Northern resident community used the area. Our lab is in the core area for the community, and over the years we built up information on a year-round basis. In 1979 we settled there permanently and started living there year-round. I guess, in summary, I bumbled my way into orca research and ending captivity, and that’s pretty much where we are!  Northern residents (Photo: Rob Lott) Northern residents (Photo: Rob Lott) Suzie: What are OrcaLab's main research aims today and how do you achieve them? Paul: Well, we started to want to see what the whales were doing in these remote places. At the beginning of 2000, we started building video systems. With the support of Japan’s NTT Data Corporation, and a Tokyo company called J-Stream, we were able to stream live feeds from three cameras to the internet. We ended up running this project for six years (double what we were promised when it began) and in the end had an audience in about 70 countries. It was very interesting to see the reaction people had to live audio and video of the orcas. We later again got involved streaming live video with a man called Charlie Weingarten, creator of a website called Explore.org. So currently we have an ability to watch and listen to the whales remotely. This is not just entertainment, but it’s exciting and valuable in terms of the information it provides. For example, last year we were able to see that two orcas visiting the rubbing beach were pregnant, and determine the gender of a young female orca. So currently, we’re doing research and gathering more information about the whales, but also being able to show people what orcas are like through the internet and gain more respect for them. It’s a way of educating people that doesn’t involve interfering with the whales' lives – we’re very committed to the idea that nature should be left alone as much as possible. We’ve also built up a very large database of recordings from groups and individuals. We have a collaboration with Professor George Tzanetakis at the University of Victoria, who heads a lab in computer sciences. Together, with great help from a PhD student named Steven Ness, we’ve managed to build an archive called the "Orchive". It houses more than 20,000 hours of recordings that we’ve made over the years. Ultimately, what we do is contribute to the understanding of the Northern resident orca population and its status. Our work has been helpful to the designation of the Blackfish Sound-Johnstone Strait area as "critical habitat" for the population. Food, ocean noise and disturbance of their habitat are the main issues at the moment, and through the data we collect we can give our thoughts and recommendations, which benefit this population of orcas.  Corky (Photo: Jessica Aditays via orcahome.de) Corky (Photo: Jessica Aditays via orcahome.de) Suzie: Tell us about Corky, the longest surviving wild-born orca in captivity... Paul: Corky was captured just before Christmas in 1969 from the Northern resident orca community. I wasn’t aware who Corky was when she was captured, but I was there when she was lifted out of the water, put on the back of a truck and ultimately taken away to Marineland of the Pacific, Los Angeles. I witnessed several of her pod mates taken away too, and others released. There were five members of her pod in Marineland in that tank. One by one they died until there were just Orky (a male) and Corky left. They were close relatives. I don’t think under normal circumstances they would mate – but they did mate in that circumstance. She became pregnant seven times and had six babies, all of whom died. The longest any of her babies lived was just 46 days. It really was a tragic situation. Eventually, Marineland was sold to SeaWorld in San Diego, and Orky and Corky were moved there. I think Orky died about 18 months after, but Corky is still there today. She came from the A5 pod, which we came to know very well. It’s one of the most common groups that we see in our area, so we have a really good idea about who Corky is and where she belongs. Knowing this, at a certain point, we decided to try and advocate for Corky to come back home. Suzie: What did you initially do to try and bring her home? Paul: At the time, SeaWorld was owned by a company called Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, a publishing company, and I bought a share in the corporation and went to their annual meeting. I made a pitch to the shareholders and I was invited to a meeting with William Jovanovich, who was the Chair of the company. We had a good conversation and I was hopeful at that point. Sadly, not too long after, that corporation sold SeaWorld to Anheuser-Busch, so we spent another long period of time trying to get through to them. We thought we were coming close to a conversation with August Busch who ran the company, but all he did was turn over our request to the SeaWorld people who were adamantly opposed to the idea that Corky should come home. Back in those days Corky’s mum was still alive. She was named 'A23' (or ‘Stripe’), and in the early days of this campaign we were hoping for a reunion of the two. But ultimately she died in the wild and that opportunity was lost. Given what we understood at that time that orcas were some of the most closely bonded creatures on the planet, it would’ve been an incredible thing to see the reunion. Suzie: And how about bringing Corky back now? Paul: In those days, what we were imagining was that we could bring Corky home and reintroduce her to the ocean, let her learn how to catch live fish again, reunite with the other whales in the ocean and then let her go free. That was the hope, but it never happened. Literal decades passed and now we’re facing the point at which Corky has been in captivity for 47 years. At this point, given her age –she’s 52 years old now– and in her condition, we came to the conclusion it was probably too risky to bring her back and set her completely free. The idea we have at the moment is to take care of Corky for the rest of her days in a "retirement home" natural ocean setting, where she would have contact with her family again. We think that would be the decent thing to do. We’re thinking of a couple of sites in Blackfish Sound, which is just around the corner from us. One is a place called Double Bay. It has some islands at the entrance which could be linked by nets. It would create a secure space inside the bay where Corky could be housed and looked after; obviously a much larger space than she has in her tank. SeaWorld would have to be involved in this because she’d have to be cared for by people she knew well, but she would at least be able to have acoustic contact with her family at the end of her life. Our attitude is that as long as Corky is alive, even though she's still in a tank, she’s still got a chance. She could come home. Corky has obviously done a huge amount for people over the years and for SeaWorld in particular, so we think doing this would be a gesture in return, giving her something back. It would be a powerful thing to do not just for orcas in captivity, but for orcas in the wild as well. Suzie: SeaWorld's approach to orca captivity has changed recently. Might this impact Corky? Paul: I can see SeaWorld’s business attitudes changing. They’re realising, (especially after “Blackfish”), that they have to do things to change public perception of what they’re doing. Ending captive breeding of orcas is a big step that has really put a limit on how long SeaWorld would survive as a business with orcas in its tanks. They are also ending their circus-type shows; exactly what they’re going to transform their shows into is a bit unclear, but they are thinking of new ways to do their business. We think that if they get involved with Corky it will be really beneficial to them as it will show that they’re changing their attitudes to orcas and where they belong. I think at this point they’re very resistant to the idea of moving all their orcas to a seaside sanctuary, (which is the project that Lori Marino and all her colleagues are working on), but it would be a step towards that and satisfy people that SeaWorld is actually progressing. Suzie: And for OrcaLab, what's your vision for the research centre going forward? Paul: In terms of where we’re going, what we’re interested in is continuing to develop techniques for learning about orcas in the wild, and to share what we hear and what we see of orcas. We’re very lucky to have Explore.org with us. They’ve got amazing technical expertise, in terms of developing the cameras and the ability to observe orcas remotely, and to share what we see and hear with people around the world. That’s where we’re going. I love the philosophy of Explore; that you can observe animals in the wild without interfering and learn a lot about them at the same time. It has been great talking with you Dr. Spong, thank you for taking time out to speak with us! You can visit the OrcaLab website here, follow on Twitter and watch the live video streams. Find out more about captive Northern resident orca Corky by visiting the Free Corky Campaign.Thanks to Stefan Jacobs and orcahome.de for photographic contributions

0 Comments

|

AuthorSuzie Hall Interviews |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed