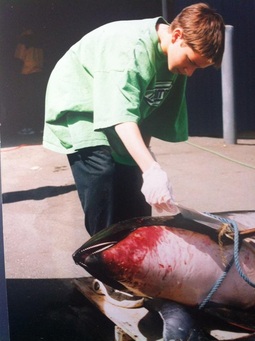

Josh with the skull of transient T44 Josh with the skull of transient T44 Josh McInnes is a 25 year-old transient researcher currently residing and working in Victoria, British Columbia in Canada. Recently graduated from a BSc in Biology, Josh has been independently studying the transient orcas off the coast of Vancouver Island for the past six years, but has been watching them for the past 14 years. Josh launched the Transient Killer Whale Research Blog (now The Transient Killer Whale Research Project) in 2011 and it acts as an open channel for transient orca news, resources and photos. “Killer whales are extraordinary animals that dominate most marine ecosystems as top predators and that is why they grab my attention.” – Josh McInnes ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Sam: When did you first realise you wanted to work with orcas? Josh: At the age of five I was into anything to do with wildlife and I ended up going to the Vancouver Aquarium. I ended up seeing my first orca that actually stuck its tongue out at me – that was pretty special. And then a few years later, at the age of 12 I witnessed my first transient [orca] hunt and that was it. That started off as my turning point into the dark areas of orcas.  Josh aged 12 dissecting his first transient kill Josh aged 12 dissecting his first transient kill Sam: Do you remember what the transients were hunting during this first wild encounter? Josh: Pacific white-sided dolphins; I remember the whole hunt very vividly. I remember sitting fishing with my cousin one day and this Pacific white-sided dolphin came screaming into the bay. These orca came in behind them and the whole harbour just went silent. And then suddenly it just exploded. The water erupted; the dolphin went flying through the air, about 20 feet, followed by a big female orca. One of the dolphins actually beached itself and died to escape these orcas. I didn’t know who they were at that age but later on I found out it was the T19 matrilineal group. I didn’t bump into that same group again until I was about 22 years of age. This was my first big encounter with transients – I would say it shaped my whole destiny. Sam: How did your first encounter with orcas in captivity compare with your first encounter with orcas in the wild? Josh: In the aquarium, one of the things that caught me as a young kid was the shape, the colour, the black and white. As a kid I thought those eye patches were their eyes, I didn’t know what they were. They’re just the coolest looking animal. I remember three orca blowing away in the tank. It left an impression on my future. Seeing them in the wild for the first time was very different. Out in Johnstone Strait, I got to see the Northern resident A pod. I grew up in the Telegraph Cove area, a number one orca hotspot and the area where orca research first started.  T60 speeding after a Dall's porpoise (Photo: Josh McInnes) T60 speeding after a Dall's porpoise (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: I was going to ask you this later on in the interview, but while we are on the topic, what are your thoughts on orca captivity? Josh: Orca research in aquariums has had its time and now I am against keeping them in captivity. After hearing the accounts of people being killed by orcas in captivity and after studying predator ecology I began to realise captivity isn’t good for these animals. Seeing something that big munching on dolphins in the wild was a bit of an eye-opener. Putting yourself in the water with captive orcas is like putting yourself in a cage with a grizzly bear – you just wouldn’t do it. Orcas are top predators. They are the largest apex predator since the dinosaurs. Most orcas in captivity now are of the resident ecotype but still, having them in captivity for me is a no-brainer, we shouldn’t be doing it. Sam: What inspired you to work with orcas and specifically transient orcas? Josh: I’ve always been fascinated by predator ecology and anything that hunts. But I’m the type of person that needs one specific focus. And the ecology of transients fascinated me ever since that first encounter. Being the top predators in the ecosystem I just find them so much more interesting to watch when it comes to studying foraging habits. They are less studied as well which means there’s a lot more out there to pursue. Sam: How did you begin your career working with orcas? Josh: I spent a lot of time working on whale watching boats as I was growing up. And then I started reading a lot of scientific papers and recording my own observations. I didn’t get much help, I am doing it independently. If you want to get paid, you work for a whale watching company, guiding for them and also conducting your research at the same time. You have to put your own money in or find funding from somewhere else. Sam: Is there anyone who has helped, inspired or mentored you along the way? Josh: My inspiration is Dr. Robin Baird. He was the first guy who really started to understand the foraging habits of transients, back in the 1980s. Robin Baird’s work helped me figure out what my passion was. I haven’t had any real mentors. Ken Balcomb [of the Center for Whale Research in Washington State] is a big resident orca guy. He’s phenomenal and his work just blows everybody away. I’ve met him a few times. But not many people are studying transients.  Example photo-ID shot (Photo: Josh McInnes) Example photo-ID shot (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: What is it that you do exactly? Josh: Right now I just graduated from a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology with a speciality in Ecology. I started late because I actually did all the field stuff first. I spent a lot of my time working out on the whale watching vessels before I went to university. At the moment, the season [of studying transients in the field] is over for me. It usually runs from April to about September, October, which overlaps with when the harbour seals are pupping. That’s when we have transients but also it’s when the weather gets nicer and we have more tourists in. Tourism is the main thing. I rely on the whale watching boats a lot. I’ve rented my own boats before but it’s too pricey right now. I take a notebook with me, I sit there and I watch. I still abide by the whale watching guidelines; I don’t go within 100m of the orcas. I sometimes talk to tourists about the whales and do my research. I collect my own pictures, I collect all my own data. The nice thing about being educated and going to school is that you start to realise there is stuff you can use, I can do statistical tests to analyse and compare my data. I record times of kills, how fast they kill, what they kill, I time their dives and their breath holds. Behaviour’s huge, it’s all about behaviour. I collect this data over and over and over. And anything unique that happens, I just sit there and watch and then at the end of the trip I write everything down: latitudes, longitudes, weather conditions, tides. I then go and compile everything that I have onto a computer. I can then work out some graphing. Sam: Why study for a degree when you were already doing what you loved? Josh: I’d seen a lot of the guys in whale watching that wished they could write papers. They wanted to do more. And then I started reading a lot of Robin Baird’s work and I realised this guy specialises in transients. Some of the stuff he wrote about made so much sense, his research and theories. I decided in the end that I wanted to make sure that I have a good standing to be able to focus on that one thing. I thought that university would be the best place to go to set a career choice. It’s good to have a degree, especially if I want to go worldwide. University can teach you how to think like a researcher which is a very important reason why I went. Thinking like that is very important.  Transient orcas T69A, T69A2 and calf T69A3 (Photo: Josh McInnes) Transient orcas T69A, T69A2 and calf T69A3 (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: How difficult are they to study – do they spend their whole time in coastal waters? Josh: They do spend their whole time in coastal waters but they constantly move around. They are very technical and complex because their foraging habits determine where they go. Like any top predator, they basically go where food is. During August and September we see a lot of transients in South Vancouver Island because that’s when the harbour seals are having their pups. The biggest problem is finding them. And especially with the whale watching boats, finding the residents is first priority, which means sometimes there’s transients around but you just don’t know they’re there and everybody goes to the residents. When transients are found, they move fast. They can move a far distance quickly. When you actually get to them, it’s a little bit easier. When I’m trying to record data it’s easier because they take longer dives. The residents are constantly going up, down, up down, for very shallow, short dives, whereas the transients don’t do that. You have to learn to recognise their habits. For example, if they’re within 200m of shore then they’re inshore foraging. If they are right up against the shore then they’re shallow foraging and they’re after harbour seals or something like that. When they are offshore it usually means they are hunting for porpoise or the odd seal. I’ve gotten to recognise really key spots to find them and one of them is right outside the harbour I work. If you have enough time and you stay with them, something pretty cool usually comes about, because they are hunting a lot of the time. They don’t socialise as often or for as long as the residents.  Transient T60C spy-hopping (Photo: Josh McInnes) Transient T60C spy-hopping (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: Where do transient orcas go when they aren’t in coastal waters? Josh: That’s a question that no one really knows, but they’ve done some tagging and most people suspect that they might go to remote regions. They are hard to predict. They could end up going up to southeast Alaska and there are a lot of unknown areas up there. They can go anywhere and you just may not see them. Transients have a diverse range. I have seen them down here [South Vancouver Island] and then two days later they’re in Robson Bight on North Vancouver Island. The transient lifestyle is coordinated to their prey; where they go, their social organisation, the size of the groups. Transients live in small groups because it is easier to hunt prey, they’re less conspicuous. And the pods are more fluid than those of the resident orcas; males and females may leave the pod if it gets too big. They are much quieter than the resident orcas. Transients are basically silent hunters, unless they’ve made a kill and then sometimes they are very vocal. Not just that, I’ve seen transients start to exhale underneath the water. They start to breathe underneath the water so that they don’t make that ‘pffooo’ sound when they come to the surface, so seals can't hear it. Even stuff like that is phenomenal for hunting. It’s really exciting to understand and model. Sam: So they haven’t been studied for too long? Josh: Michael Bigg distinguished them in the 1980s; he thought they were basically outcasts of the resident pods and they turned out to be a different ecotype altogether. And then Robin Baird, his thesis was on transient orcas from 1986 to 1993. He really started the transient studies. You barely see anyone specifically studying the transients, although there are a few key researchers. Sam: What do transient orcas eat? Do you ever feel sympathy for the mammals they are munching on? Josh: They eat harbour seals the majority of the time – the reason being they are defenseless little things and there are so many here – but also they eat harbour and Dall’s porpoise, Steller and California sea lions, Northern elephant seals, Pacific white-sided dolphins and large baleen whales. The largest animal I’ve seen them attack was a minke whale. They were taking chunks out of it, they didn’t kill it. What is interesting is that each pod hunts in a specifically different way from the others; one group might hunt seals while another will specifically stay offshore and hunt porpoise. Some do both. Dall’s porpoise is the hardest animal to catch, you have to be a really experienced orca to catch them. I feel sympathy the odd time, but usually I don’t because I understand how it is and that’s how top predators act and being really into the ecology of top predators, I don’t seem to feel that remorse.  Ca60 dwarfing female orcas (Photo: Josh McInnes) Ca60 dwarfing female orcas (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: Transient and resident orcas never mix but there have been instances of aggression displayed by the fish-eaters toward the mighty mammal killers. Why do you think this is? Josh: Transients are larger in body size and weight. But you have to remember that fish-eaters, the residents, have numbers on their side. J-pod is the smallest of the Southern resident pods and still has 25 or 26 animals at the moment. That’s a lot more than five transients. We don’t see any kills though, not between orcas. But they don’t like each other. I think it’s one of the most interesting feuds in the animal kingdom to study. Sam: Do you have any favourite orcas that you study and if so, why? Josh: I don’t really study him but he’s known as Ca60, a transient from the Californian community that they call ‘Can-Opener’ and he is massive. I’ve never seen a dorsal fin on a whale like that. It was over six-foot, but the width, it was all about the width. It was a phenomenal size. I have a picture of him with the females that were there and they look like dolphins, not orcas. He was just unbelievably huge. I’ve never seen anything like that. The transient groups I study can change from year-to-year so I don’t really get the chance to become attached to any individuals. Sam: What conservation threats do transients face? Josh: The transients are doing quite well at the moment, they’re looking pretty good. And that says a lot because they are actually the most toxic marine mammal out there. Their number one threat is pollution. It is just unbelievable the amount and concentration that these orcas have in their systems. Peter Ross did most of the work on the toxicology of transient orcas and they are contaminated with PCBs and DDTs, way more than residents – exponentially more. Transients are top of the food chain and they eat everything, except for fish of course. If you find them on the beach dead, they are treated as toxic waste. These pollutants are still getting into their system. It’s very disturbing. And there’s not a lot we can do about it. Whale watching can sometimes affect transient hunting success too, sometimes they miss prey. I don’t know whether that’s the boat noise. The majority of the time they do get the prey. Other than that we just need to monitor their prey and make sure they stay stable, make sure the harbour seal population stays stable. We’ve got to make sure we know the ecology not just of the transients but of the overall ecosystem that the transients are living in. We have to make sure that we protect not just the orcas, but everything that is around them. There are about 277 transient orcas recorded here now. There were four or five new calves last season who are doing great. Sam: Canada is a busy hotspot for orca watching – what are your thoughts on the impact that whale watching can have on the animals versus the value of orcas to the local economy? Josh: I think that we’ve got to start thinking less about the money that the whales make for us and instead about real love for it. I’m a pro-whale watcher but there are too many boats sometimes watching the animals. It’s important that the enforcement officers are knowing what is going on though. Sometimes the whales pop up by the boats and if you’re engines are off, you are a sitting log and you are no danger to the orcas. It’s difficult to govern. Sam: What relevance / significance do orcas have to Canada’s First Nations people? Josh: Native people have a lot of respect for wildlife. They are the first on the scene when something needs to be done. They are one of the big tools of conservation that we can rely on as being there for the animals. First Nations people worship orcas; I think orcas are also a sign of strength and an animal of awe. It’s bad voodoo to kill a killer whale.  Transient T41A (Photo: Josh McInnes) Transient T41A (Photo: Josh McInnes) Sam: Now, for some lighter questions. I am performing a short study: they say that pets look like their humans – so I was wondering whether researchers are like their study subject. Describe transient orcas and yourself in three words. Josh: The transients would be stealthy, intelligent and remarkable. And I’d describe myself as logical, investigative and natural. Sam: Very interesting. What are your thoughts on the Orca Aware campaign here in the UK? Josh: I think it [Orca Aware] is amazing and that you are spreading the word on issues that need to be realised by society. Sam: Are there any hot topics you feel we should be focusing our attentions on? Josh: I feel politics in science is one that should be brought out and showed. I feel there needs to be more employment opportunities with marine wildlife. Sam: Orca Aware is a campaign for everyone – even people who don’t know too much about orca. How would you encourage someone who has no previous interest in orcas to start learning about them? Josh: I strongly encourage people to go out to the beach; go and hang out in nature in general. Go and make a connection with the marine wildlife found there – it doesn’t have to be orcas. Sam: And finally, do you have any advice for young aspiring orca researchers / conservationists out there? Josh: The best thing to do as a researcher is to find someone out there who you really connect with that inspires you as a researcher yourself. Somebody who’s writing really leaves an impression. Read as much as you can and find a way to get out there and research these animals. Send emails out to research projects, see if they are taking on volunteers. Find out what research is going on in your country – it may not be with orcas, but any experience is relevant. Thank you for your time and insight Josh, I have really enjoyed talking with you! Visit The Transient Killer Whale Research Project

|

AuthorSam Lipman Interviews |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed